Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) is an idiopathic, hereditary, and generalized form of epilepsy. JME accounts for approximately 5%-10% of all cases of epilepsy. JME usually manifests between 12 and 18 years of age. JME is characterized by the presence of absence (20-40%), myoclonic (100%), and generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) (85-90%) seizures.

Clinical Features

Myoclonic seizures are the defining feature and are required for the diagnosis of JME and very rarely can be the only type of seizure present. Typically absence seizures are the first to occur in JME. They usually occur 3 to 5 years before the onset of myoclonic or GTC seizures and can happen as early as 5 to 6 years old. Myoclonic seizures present with short, bilateral jerking motions of the arms and legs that do not cause consciousness to be lost and often occurs 30 minutes to an hour after waking up in the morning. JME is typically triggered by sleep loss, alcohol consumption, mental stress, worry, and exhaustion. GTC seizures typically develop many months after myoclonic seizures begin. About 30-40% of JME patients are photosensitive and these patients tend to have earlier onset of seizures. There is an increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, mood disorder, and personality disorders in patients with JME[1].

EEG

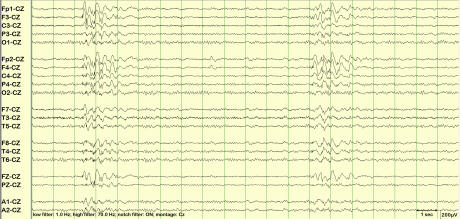

Fig. 1: 5Hz predominantly bifrontal polyspike and wave discharges

Fig. 1: 5Hz predominantly bifrontal polyspike and wave discharges

- Interictal EEG is abnormal in the majority of patients with JME.

- The typical EEG in JME shows diffuse, symmetric, bilateral 4 to 6 hertz (Hz) polyspike and wave discharges(figure 1) with a fronto-central predominance.

- The background has normal alpha rhythm

- Ictal or continuous EEG recording shows 10-16 Hz polyspike discharges with myoclonic jerks. The spikes correlate with myoclonic jerks

- The abnormalities are often seen during the transition from sleep to awakening.

- The EEG findings in GTC (low voltage fast activity with spike and wave discharges) and absence seizures (generalized 3 Hz spike and wave discharges) associated with JME are similar to those seen with other epilepsies

MRI

Genetics

- A positive family history in approximately 50% of cases. The genetics of inheritance is not fully understood, but a multifactorial mechanism is suspected

- Five Mendelian JME genes have been identified, namely, CACNB4, CASR, GABRa1, GABRD, and Myoclonin1/EFHC1[4]

- Three SNP alleles in BRD2, Cx-36, and ME2 and microdeletions in 15q13.3, 15q11.2, and 16p13.11 also contribute risk to JME[4]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes childhood or juvenile absence epilepsy, eyelid myoclonia with absences, progressive myoclonic epilepsy, photosensitive occipital epilepsy, epilepsy with grand mal seizures upon awakening, hypnogogic myoclonus (hypnic jerk), and non-epileptic seizures.

Treatment / Management

- Most patients respond to monotherapy with Valproic acid which is the drug of choice

- levetiracetam, lamotrigine, topiramate, and zonisamide are other options[5]

- Lamotrigine can worsen myoclonic seizures but is still effective in controlling other seizure types in JME

- Clonazepam is also effective against myoclonic seizures

- Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin (sodium channel blocking agents) are contraindicated since they can worsen myoclonic and absence seizures.

- vigabatrin, tiagabine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and primidone are also avoided

- JME becomes intractable in a small number of patients who would need combination therapy with Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) also as an option.

- JME needs life long treatment with AEDs

- Avoidance of triggers is important - alcohol, fatigue,stress, sleep deprivation, flashing lights etc

References

[PMID: 17201708] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00828.x]

[PMID: 18227991] [DOI: 10.1007/s00415-008-0745-6]

[PMID: 29344465] [PMCID: 5767493] [DOI: 10.14581/jer.17013]

[PMID: 23756480] [DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.033]

[PMID: 21494841] [DOI: 10.1007/s11940-011-0131-z]

Discussion