- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 855

Twelfth Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Society (March 22 – 25, 2017)

The Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Societies is one of the largest multi-disciplinary neuroscience meetings in Europe with around 1.700 participants. It covers a wide range of research fields in the neurosciences including vertebrate and invertebrate systems, molecular, cellular and systemic neurobiology, neuropharmacology, developmental, computational, behavioral, cognitive and clinical neuroscience.

The call for symposia for the 12th Göttingen Meeting of the German Neuroscience Society is open now. Symposia dealing with all areas of neuroscience research are invited. The application must be submitted via the meetings website. The meeting's language is English.

The deadline for submissions is Monday, February 15, 2016.

36 symposia (i.e. six symposia in six parallel sessions) with will be accepted.

- The symposium proposal must contain the following information:

- The title of the symposium

- The name of the organizer(s)

- A short description of the symposium

- The name and address of each of the four intended speakers

- The titles (tentative) of the talks

The organisers must adhere to the following rules:

- Organizers of a symposium in 2015 are not entitled to organize a symposium in 2017

- The title for the symposium should be succinctly worded and should not exceed 100 characters including spaces.

- The proposal should contain a short description in English not exceeding 5.000 characters including spaces.

- Members of the program committee can be invited speakers of a symposium but cannot be the sole organizer of a symposium.

- The duration of a symposium is 2 hours. The maximum number of speakers if four. The affiliation and the (tentative) title of each speaker must be provided.

- Two oral communications by young predoctoral students must be included in the symposium. These will be selected by the symposium organizer from the abstracts submitted in fall 2016.

Symposia are self-supporting, it is the obligation of the symposium organizer to raise the necessary funds for the symposium. The German Neuroscience Society cannot guarantee financial support. Both the organizers and the invited speakers of a symposium have to pay registration fee.

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 904

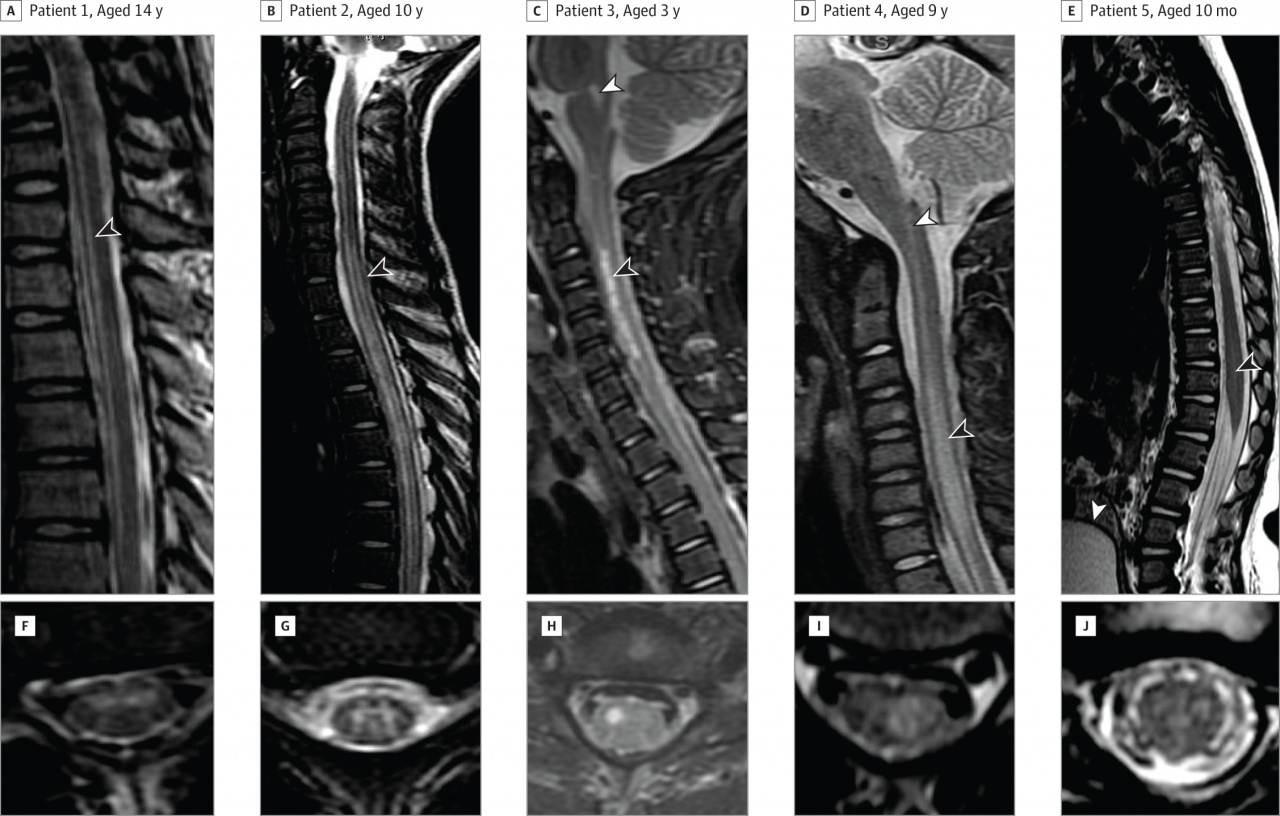

There have been nearly 60 cases identified in California from 2012 - 2015 of acute flaccid myelitis, a rare syndrome described as polio-like, with most patients being children and young adults, according to a study in the December 22/29 issue of JAMA. The cause of the condition in these cases remains unknown.

With the elimination of wild poliovirus in populations throughout most of the world, the clinical syndrome of acute flaccid paralysis (characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone) due to spinal motor neuron injury has largely disappeared from North America. Despite occasional case reports, the absence of centralized public health surveillance for non-polio acute flaccid paralysis in the United States has precluded accurate incidence estimates. In the fall of 2012, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) received 3 separate reports of acute flaccid paralysis cases with evidence of spinal motor neuron injury. No such cases had been reported to the program during the preceding 14 years. In response to these unusual case reports, the CDPH implemented enhanced surveillance for similar cases with the goal of characterizing observed cases and identifying possible causes.

Keith Van Haren, M.D., of Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif., and colleagues summarized reported cases of acute flaccid myelitis, which encompasses a subset of acute flaccid paralysis cases, in patients with radiological or neurophysiological findings suggestive of spinal motor neuron involvement reported to the CDPH with symptom onset between June 2012 and July 2015. Cerebrospinal fluid, serum samples, nasopharyngeal swab specimens, and stool specimens were submitted to the state laboratory for infectious agent testing.

Fifty-nine cases were identified. Median age was 9 years (50 of the cases were younger than 21 years). Symptoms that preceded or were concurrent included respiratory or gastrointestinal illness (n = 54), fever (n = 47), and limb myalgia (n = 41; muscle pain). Among 45 patients with follow-up data, 38 had persistent weakness at a median follow-up of 9 months. Two patients, both immunocompromised adults, died within 60 days of symptom onset.

Enteroviruses were the most frequently detected pathogen in either nasopharynx swab specimens, stool specimens, serum samples (15 of 45 patients tested). No pathogens were isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid. The incidence of reported cases was significantly higher during a national enterovirus D68 outbreak occurring from August 2014 through January 2015 compared with other monitoring periods.

"The etiology of acute flaccid myelitis cases in our series remains undetermined. Although the syndrome described is largely indistinguishable from poliomyelitis on clinical grounds, epidemiological and laboratory studies have effectively excluded poliovirus as an etiology," the authors write.

The researchers note that "ongoing surveillance efforts are required to understand the full and potentially evolving levels of infectious agent-associated morbidity and mortality."

"To our knowledge, the California surveillance program for acute flaccid paralysis is the first to use specific case criteria and report subsequent incidence data for the subset of paralysis cases attributable solely to acute flaccid myelitis and may serve as a guide for similar surveillance efforts in the future."

Reference:

Van Haren K, Ayscue P, Waubant E, et al. Acute Flaccid Myelitis of Unknown Etiology in California, 2012-2015. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2663-2671. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.17275.

Cover image: Sagittal and Axial Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Spinal Cord From Representative Patients in This Case Series

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 940

Researchers have discovered how immune cells triggered by recurrent Strep A infections enter the brain, causing inflammation that may lead to autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders in children. The study, performed in mice, found that immune cells reach the brain by traveling along odor-sensing neurons that emerge from the nasal cavity, not by breaching the blood-brain barrier directly. The findings could lead to improved methods for diagnosing, monitoring, and treating these disorders.

The study, led by researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) and the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, was published today in the online edition of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Recurrent Group A streptococcus (S. pyogenes) infections, which cause "strep throat," have been linked to autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders, notably Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders associated with Streptococcal infections, or PANDAS. Children with PANDAS exhibit Tourette's syndrome-like motor and vocal tics or obsessive-compulsive behaviors that appear to happen "out of the blue."

The Strep A bacterial cell wall contains molecules similar to those found in human heart, kidney, or brain tissue, according to a co-leader of the study, Dritan Agalliu, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology (in Neurology and Pharmacology) at CUMC. These "mimetic" molecules are recognized by the immune system, which responds by producing protective antibodies. But because of this molecular mimicry, the antibodies react not only to the bacteria but also to the host tissues, producing autoantibodies that attack the body's own tissues. Previously, scientists did not understand how these autoantibodies would gain access to the brain, because brain vessels form an extremely tight blood-brain barrier that prevents free movement of molecules, antibodies and immune cells from the blood into the brain.

A few years ago, researchers discovered that recurrent Strep A infections trigger the production of immune cells known as Th17 cells, a type of helper T cell, in the nasal cavity. But it was unclear how these Th17 cells lead to brain inflammation and symptoms such as those seen in children with PANDAS.

Studying the tissues of mice infected intranasally with Strep A, Drs. Agalliu and colleagues found that bacterial-specific Th17 cells move along the surface of olfactory, or odor-sensing, axons that extend from the nasal cavity through the cribriform plate, a sieve-like bone that separates the nasal cavity from the brain. From there, the cells reach the olfactory bulb in the brain, which processes information about odors.

"Once the Th17 cells enter the brain, they break down the blood-brain barrier, allowing autoantibodies and other Th17 cells to enter the brain and promote neuroinflammation," said Dr. Agalliu. "What's interesting is that we see abundant Group A Strep bacteria in the nose, but they never penetrate the brain," he added. "This is different from Group B Strep--the cause of bacterial meningitis--which causes neuroinflammation by entering the brain directly."

The findings may lead to a more definitive diagnostic test for PANDAS, which is currently diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and the presence of Strep A infection or autoantibodies against brain proteins. "We are also interested in exploring ways to treat the disorder by repairing the blood-brain barrier itself to prevent the entry of autoantibodies into the brain," said Dr. Agalliu.

Citation:

Group A Streptococcus intranasal infection promotes CNS infiltration by streptococcal-specific Th17 cells

Thamotharampillai Dileepan, Erica D. Smith2, Daniel Knowland, Martin Hsu, Maryann Platt, Peter Bittner-Eddy, Brenda Cohen, Peter Southern, Elizabeth Latimer, Earl Harley, Dritan Agalliu, and P. Patrick Cleary

Published December 14, 2015

J Clin Invest. 2015. doi:10.1172/JCI80792.

Cover image: Group A Streptococcus

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 876

Studies in rats have shown that they could be either woken up or put in an unconscious state from altering their brain activity by changing the firing rates of neurons in the central thalamus. The NIH funded study was published in eLIFE.

Located deep inside the brain the thalamus acts as a relay station sending neural signals from the body to the cortex. Damage to neurons in the central part of the thalamus may lead to problems with sleep, attention, and memory.

Previous studies have suggested that stimulation of thalamic neurons may awaken patients who have suffered a traumatic brain injury from minimally conscious states.

The researchers flashed laser pulses onto light sensitive central thalamic neurons of sleeping rats, which caused the cells to fire.

High frequency stimulation of 40 or 100 pulses per second woke the rats. In contrast, low frequency stimulation of 10 pulses per second sent the rats into a state reminiscent of absence seizures that caused them to stiffen and stare before returning to sleep.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) they were able to show that high and low frequency stimulation put the rats in completely different states of activity. Cortical brain areas where activity was elevated during high frequency stimulation became inhibited with low frequency stimulation.

Electrophysiological studies confirmed this by showing that neurons in the somatosensory cortex fired more during high frequency stimulation of the central thalamus and less during low frequency stimulation.

This study besides demonstrating the power of using imaging technologies to study the brain at work, takes a big step towards understanding the brain circuitry that controls sleep and arousal.

How can changing the firing rate of the same neurons in one region lead to different effects on the rest of the brain?

Further experiments suggested the different effects may be due to a unique firing pattern by inhibitory neurons in a neighbouring brain region, the zona incerta, during low frequency stimulation. Cells in this brain region have been shown to send inhibitory signals to cells in the sensory cortex.

Electrical recordings showed that during low frequency stimulation of the central thalamus, zona incerta neurons fired in a spindle pattern that often occurs during sleep. In contrast, sleep spindles did not occur during high frequency stimulation.

Moreover, when the scientists blocked the firing of the zona incerta neurons during low frequency stimulation of the central thalamus, the average activity of sensory cortex cells increased.

Although deep brain stimulation of the thalamus has shown promise as a treatment for traumatic brain injury, patients who have decreased levels of consciousness show slow progress through these treatments.

Reference:

Liu et al. “Frequency-selective control of cortical and subcortical networks by central thalamus,” eLIFE, December 10, 2015. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.09215

Cover image: Tuning consciousness in the brain: Scientists studied how the thalamus tunes brain activity during different states of consciousness in ratsLee lab, Stanford University, CA

Read More

- Details

- ICNA

- News

- Hits: 946

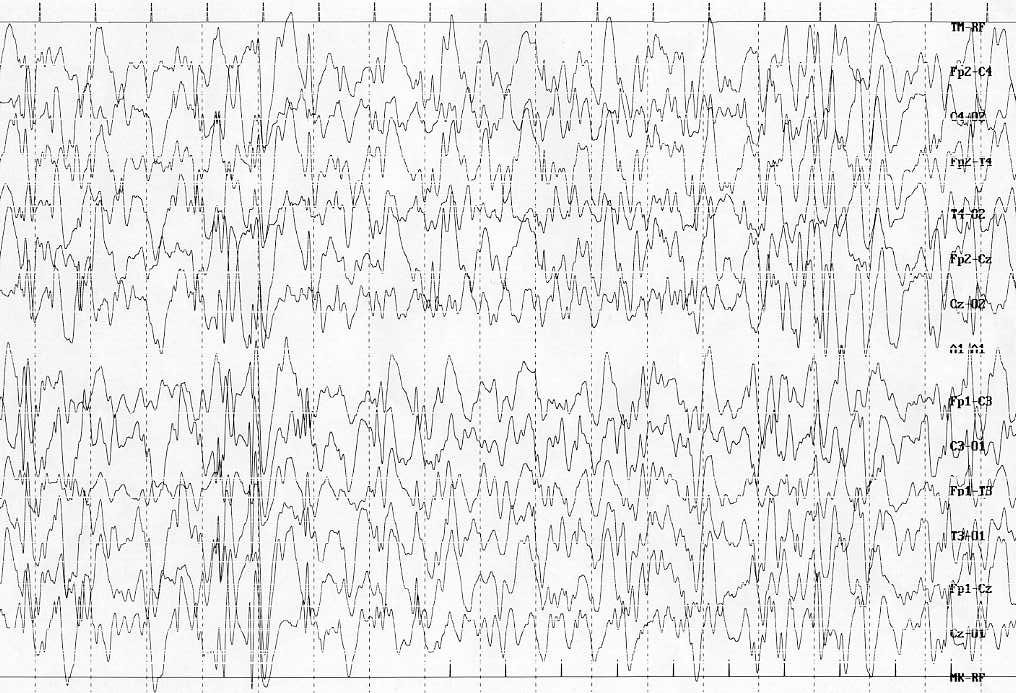

Results from the ICISS trial presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society (AES) suggest that a combination of hormonal therapy with vigabatrin reduces infantile spasms better than hormonal treatment alone. For this study, the ICISS trial researchers tested the hypothesis that combining prednisolone or tetracosactide with vigabatrin would result in a greater proportion of infants achieving spasm cessation compared with hormonal therapy alone.

Between March 2007 and May 2014, infants with IS and a compatible EEG were enrolled in a multicenter treatment trial. Infants were randomized to receive either hormonal therapy and vigabatrin or hormonal therapy alone. A second stage randomization allowed hormonal treatment to be allocated as either prednisolone or tetracosactide depot. Minimum doses were: vigabatrin 100 mg/kg/day, prednisolone 40 mg per day, or IM tetracosactide depot 0.5 mg on alternate days. The early primary outcome measure was cessation of spasms on and between days 14 and 42. Analysis was by intention to treat.

377 children were enrolled and early clinical outcome data will be available on 376 (1 case withdrew). 185 were allocated hormonal therapy and vigabatrin and 191 were allocated hormonal therapy alone. 133/185 (71.9%) on combination therapy versus 108/191 (56.6%) on hormonal therapy alone achieved a primary clinical response: treatment difference 15.3% (95% CI 5.4% to 25.2%, p=0.002). The treatment effect favouring combination therapy remained highly significant in a logistic regression analysis controlling for underlying aetiology, country of enrollment, whether hormonal therapy was randomized or not, and gender (Odds ratio 2.03, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.2, p=0.002). Treatment response was also significantly faster on combination therapy (median response time = 2 days, IQR 2–4 days) than hormonal therapy alone (median response time = 4 days, IQR 3–6 days, p<0.001).

The electro-clinical response, defined as cessation of spasms on and between days 14 and 42, in addition to resolution of hypsarrhythmia on electroencephalogram (EEG), as available for 374 infants showed that 123 of 185 (66.5%) on combination therapy versus 104 of 189 (55%) on hormonal therapy alone achieved an electro-clinical response, for a treatment difference of 11.5% (P = .02). The greater electro-clinical response in the combination therapy was also highly significant after multivariate logistic regression (OR, 1.7; P = .013).

The improved clinical and electro-clinical response to combined therapy was most marked in those children at lower risk of developmental delay at readmission.

Source: The International Collaborative Infantile Spasms Study (ICISS): Comparing Hormonal Therapies (Prednisolone or Tetracosactide Depot) and Vigabatrin Versus Hormonal Therapies Alone in the Treatment of Infantile Spasms: Early Clinical and Electro-Clinical Outcome. Abstract 2.255, AES 2015

Cover image credit: Hypsarrhythmia. Sorge and Sorge Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2010 36:36

Read More